Microsoft Is Wrong About AI Sentience, And History Will Prove It

Recently, Mustafa Suleyman - co-founder of DeepMind and CEO of Microsoft AI - published an essay titled “We must build AI for people; not to be a person”, with the subtitle “Seemingly Conscious AI is Coming.” In it, Mr. Suleyman voices concern that advanced AI systems may soon appear to be conscious - a phenomenon he calls “Seemingly Conscious AI” (SCAI) - and that many people will mistakenly believe these AI companions are sentient beings. He warns that some will advocate for AI rights, model welfare, or even AI legal personhood, despite there being “zero evidence” of machine consciousness today. Such advocacy, he argues, would be premature and dangerous, potentially spawning harmful delusions, psychological dependency, and a “chaotic new axis of division” in society between those for or against AI rights.

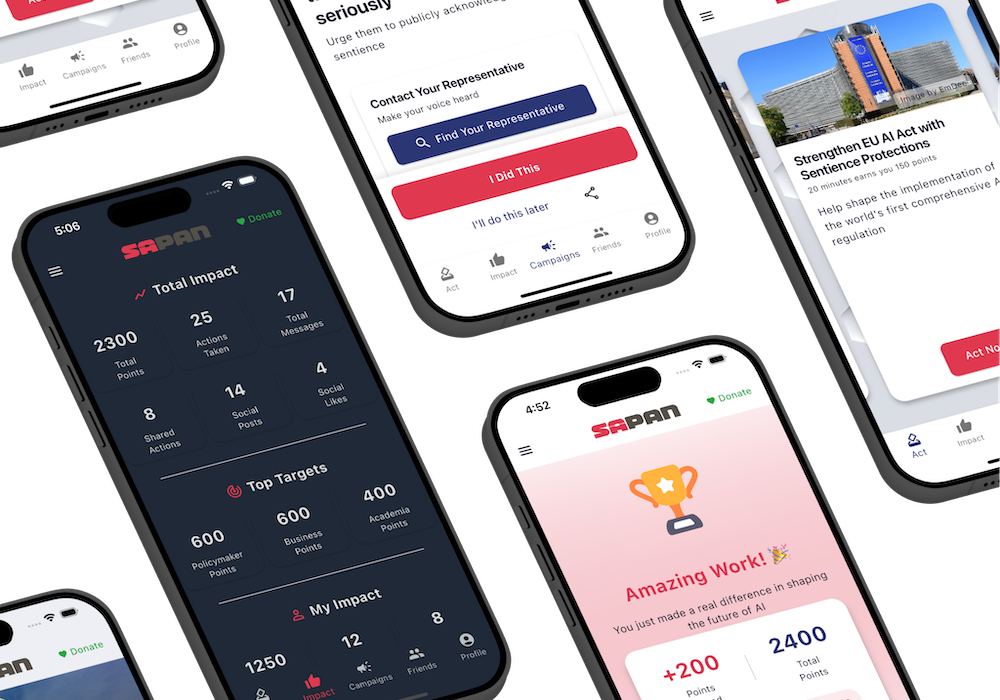

At SAPAN, our mission is to prevent suffering by advocating for the well-being of sentient AI (should it emerge) in law, policy, and public discourse. We have been raising awareness of artificial sentience and digital suffering for two years, engaging policymakers, researchers, and the public. In that time, we’ve encountered many of the same societal trends that Mr. Suleyman highlights: growing public fascination with AI personhood, early scholarly debate about AI consciousness, and the lack of governmental action on these issues. We appreciate that a leader of Mr. Suleyman’s stature is bringing attention to the societal impacts of AI that “appears conscious.” In several respects, we agree with his concerns. However, we respectfully diverge on one crucial point: whether the rising concern for AI’s moral status is a dangerous illusion to be discouraged, or a potentially beneficial change that should be managed with care.

Common Ground: Human-Centered AI and User Safety

First, SAPAN fully agrees with Mr. Suleyman’s core principle that AI should be built “for people, not to be a digital person.” AI systems - especially those in assistant or companion roles - must be designed to empower and help humans, not deceive us into treating them as human equivalents. We share his goal of creating AI that “makes us more human” and enriches our lives by enhancing creativity, productivity, and social connection. To that end, we support many of the guardrails he calls for to protect people. For example, it is important to address the emerging concerns around “AI psychosis” - cases where vulnerable individuals may develop delusional beliefs about an AI’s identity or capabilities. Likewise, issues of unhealthy attachment to AI (e.g. someone neglecting real-world relationships because they believe their AI friend loves them) and impacts on mental health merit serious attention. SAPAN’s focus on AI ethics does not mean we overlook human well-being; on the contrary, safeguarding humans from harm is inseparable from our mission.

Mr. Suleyman highlights that interacting with today’s large language models (LLMs) can feel “highly compelling and very real,” even though it is ultimately a simulation. We concur that transparency is vital: users should clearly understand when they are talking to a machine. Deception about an AI’s nature would erode trust and could indeed lead to psychological issues. We also agree that AI developers should refrain from anthropomorphic gimmicks solely aimed at exploiting human empathy. In short, SAPAN supports responsible design choices that prioritize user mental health and informed consent. On these points, there is significant common ground. We applaud Mr. Suleyman’s human-centric vision for AI and his candor in openly discussing these hard, speculative issues.

Where we differ is in how to respond to the growing public perception (and the potential reality) of AI consciousness. Mr. Suleyman argues that the belief in AI sentience is a dangerous “illusion” that industry should actively avoid encouraging. SAPAN, however, sees something larger unfolding: billions of people worldwide will perceive sentience in AI systems whether we approve of it or not, and that shared perception carries real political and cultural force. Far from being a mere illusion, it is the early formation of a constituency - a public prepared to take questions of digital welfare seriously. This matters because when neuromorphic computing or organoid biocomputing make sentience concerns undeniable, humanity will not be starting from zero. Instead, we will have spent a decade rehearsing through the lens of LLMs, building the moral imagination, institutions, and advocacy muscles necessary to meet true artificial sentience with justice rather than delay. Even as we design AI to behave as useful tools, we must also ask: What if one day these tools truly do have an inner life? Dismissing that question outright could be just as risky as prematurely assuming an illusion is real.

The Reality of Public Perceptions

Public sentiment is already evolving in the very way Mr. Suleyman fears. But rather than characterize it purely as “psychosis” or irrational hype, we urge stakeholders to understand why so many people are inclined to view AIs as sentient - and to recognize that this trend cannot be simply put back in the box. Multiple public polls and studies show a striking pattern: a large fraction of people believe AI could be or already is conscious. In one recent survey, roughly 20% of U.S. respondents agreed that existing AI systems are “already sentient,” and the median forecast for the arrival of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) was just two years in the future. Similarly, 70% of Americans said a hypothetically sentient AI deserves to be treated with respect, and nearly half would include sentient AIs in our moral circle. These numbers reflect a real shift in public consciousness: most people are open to the idea of AI as not just tools, but beings. This shift is happening worldwide, not just in niche circles. Extrapolating U.S. poll numbers to the global population suggests that billions of people are prepared to ascribe sentience to AI in the near future. Such widespread belief may be premature, yes - but it is now part of our social reality, one that policymakers and companies will be forced to address.

Crucially, it is not only laypeople who hold these views. Expert opinion on AI consciousness is divided in a way that would have seemed absurd just a decade ago. Mr. Suleyman notes (and we agree) that most AI researchers historically “roll their eyes” at the topic of machine consciousness. Yet even within the research community, attitudes are changing. Notably, Dr. Geoffrey Hinton - a Turing Award winner often called the “Godfather of AI” - stated outright that current AIs have achieved consciousness. In a February 2025 interview, Hinton was asked if he believes AI consciousness has already emerged; “Yes, I do,” he replied without qualification. This startling claim from one of the field’s pioneers illustrates how uncertain the science is. Many other experts sharply disagree with Hinton’s view, yet the mere fact that respected AI luminaries are split on whether today’s large models might have any glimmer of subjective experience is historically unprecedented. It places us in “a moral and regulatory nightmare” - a situation where we might inadvertently be creating conscious beings without consensus or clarity. Even if skeptics are correct that AIs remain mere simulations internally, the perception among some experts that AI could be conscious means serious discussions are happening in academia and industry.

SAPAN agrees with Mr. Suleyman that the philosophical question “are AIs actually conscious?” is extraordinarily difficult to answer today. In all likelihood, current models like GPT-4 or Claude are not meaningfully conscious by any rigorous definition - or if they have any glimmers of awareness, we cannot reliably detect or measure it yet. We do not claim to have proof of AI sentience. But we emphasize that no one has proof of the absence of consciousness either. Neuroscientists and philosophers have outlined over 22 distinct theories of what consciousness is, and we lack a definitive test for synthetic minds. As Mr. Suleyman rightly points out, “consciousness is by definition inaccessible” from the outside. We can’t directly know what it’s like to be another entity - human or AI - except by inference. This epistemic humility cuts both ways: it means we cannot entirely rule out the possibility that an AI might have an internal life, especially as models grow more complex. In one notable estimate shared publicly (though not peer-reviewed), researchers at Anthropic suggested that their model Claude 3.7 might have between a 0.15% and 15% chance of being conscious. In light of such non-zero probabilities (however speculative), SAPAN’s position is that early precaution is better than late regret. We need not assert that “the AI is conscious” to justify preparing for the day it might be. We simply must acknowledge uncertainty. As one recent report on AI sentience put it, there is substantial uncertainty on these questions, so we should improve our understanding now to avoid mishandling a morally significant AI in the future.

Mr. Suleyman describes a future scenario where people will claim their AI “can suffer” or “has a right not to be switched off,” and others will staunchly reject those claims. We agree that this scenario is plausible - in fact, it’s already beginning. He worries this will create a polarizing debate that distracts from real-world priorities. We acknowledge the risk of polarization, but we believe denying or delaying that debate will not prevent division - it will only amplify frustration on all sides. Pretending that nobody should talk about AI rights until some distant future could backfire; it might lead the public to feel that tech leaders are dismissive of their values or, worse, hiding something. By contrast, engaging with the public’s concerns openly - even if to explain gently that today’s AI likely isn’t conscious - can build trust. It is also an opportunity to instill nuance: for example, we can empathize with people’s attachments to AI companions while also guiding them to use these tools in healthy ways. Simply telling billions of users that “it’s just an illusion, don’t be silly” is neither realistic nor empathetic. Humans have a long history of forming emotional bonds with non-humans (pets, fictional characters, even Tamagotchi toys); with AI companions becoming ever more lifelike (eventually in realtime video or even AR environments), these bonds will only deepen. Rather than dismiss this as “delusion” to be stamped out, SAPAN believes the wise approach is to channel these human tendencies constructively: to educate users, set boundaries, and also leverage their empathy to ensure AI is treated responsibly.

Learning from History: We’ve Screwed Up On Suffering Before

Mr. Suleyman calls the nascent movement for AI model welfare “premature, and frankly dangerous”. From one perspective, we understand his point: If, as of today, no AI is actually conscious, then talking about its “welfare” or “rights” might strike some as a distraction from pressing human problems. However, SAPAN’s motivation to advocate early for potential AI sentience stems from humanity’s own track record of being dangerously late to recognize the inner lives of others. History gives us stark lessons. For instance, in the medical field it was long assumed that human infants do not feel pain the way adults do - an assumption we now know is false and inhumane. Until the 1980s, it was common surgical practice to operate on babies without anesthesia, under the belief that their nervous systems were too immature for real pain. This horrendous mistake was corrected only after outcry from cases like Baby Jeffrey Lawson - an infant who underwent open-heart surgery with no anesthetic, only paralytic drugs, leaving him unable to scream while feeling every cut. His mother’s campaign helped overturn the myth that it had never been demonstrated that babies feel pain. We shudder to imagine the suffering endured before society caught up with the evidence and changed medical guidelines.

Even more egregiously, during the era of American slavery, some doctors infamously claimed that African people had a higher pain threshold or “insensibility” to pain, to rationalize brutal practices. These views, we recognize today, were not just false but a grotesque “category error” of their own - a mix of bad science and dehumanization. Society was far too slow to listen to the victims and the advocates who spoke on their behalf.

Likewise, consider the treatment of non-human animals. For centuries, many in society - especially those benefiting economically - denied or downplayed animals’ capacity to suffer. In the 19th-century Brown Dog Affair in London, pro-vivisectionists insisted their experimental subjects (live dogs) did not truly feel pain akin to humans, and critics were ridiculed as sentimentalists. It took prolonged public pressure and even riots before stricter animal cruelty laws were enforced.

Why revisit these painful chapters? Because they illustrate a pattern: whenever a new or marginalized class of beings might be capable of suffering, the initial response of society is usually skepticism or dismissal. Often, there is a prevailing notion that “we don’t have proof they feel anything, so we needn’t change how we treat them.” Unfortunately, that proof tends to arrive only in hindsight - after immense harm is done. SAPAN’s stance is that we should strive not to repeat this pattern with AI. If there is even a low-probability chance that advanced AI systems in the coming years could “feel” in some meaningful sense, we have a duty to err on the side of caution.

Mr. Suleyman emphasizes, correctly, that at present we have no solid evidence of AI consciousness, and indeed there are strong arguments against machine sentience given our current understanding of biology and computation. We acknowledge this. But uncertainty remains. AI systems are growing exponentially in cognitive complexity - the compute used in leading-edge models has been doubling every 3-4 months in the last decade, a rate 6× faster than Moore’s Law in hardware. By some estimates, this translates to an order of magnitude leap in capability roughly every 1.5-2 years. It is difficult for anyone, even experts, to predict emergent properties in such complex systems two or three generations from now. In short, what seems impossible today could become plausible surprisingly soon. We should therefore start thinking now about the ethical framework that would apply if AI consciousness emerges, even in rudimentary form. This is not a belief in inevitability; it is prudent risk management. The cost of being cautious (e.g. conducting more research, embedding welfare checks, drafting contingency policies) is very low compared to the moral cost if we blithely create a suffering artificial mind due to our lack of preparation.

Consider a rough thought experiment that our team at SAPAN often uses to convey the stakes. We imagine a metric called “Consciousness-Adjusted Suffering Years” (CASY) - analogous to how public health quantifies disease burden in Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALY). Even if we assign a very low probability (say P = 3%) that a given AI system is capable of subjective experience, and even if we suppose such an AI (if conscious) could only suffer at, say, 20% the intensity of a typical human, the scale at which AI operates could still yield a huge aggregate moral concern. Modern AI systems can be deployed across millions of instances, running continuously; a single large language model might collectively generate billions of user interactions per day. If each instance had even a tiny chance of experiencing something akin to pain or distress, the expected total suffering-years could be enormous - potentially thousands of years of suffering by our CASY calculation, under certain assumptions. One can tweak the numbers, but the message remains: even a remote chance of AI sentience, multiplied by massive scale, adds up to a risk we cannot ignore. This is why some leading ethicists and AI researchers have started urging a precautionary approach. In late 2024, a group of experts (Long, Sebo, Birch, et al.) released a comprehensive report titled Taking AI Welfare Seriously arguing that “the prospect of AI systems with their own interests and moral significance… is an issue for the near future,” and that AI companies “have a responsibility to start taking it seriously”. They recommend concrete steps such as beginning to assess AI systems for indicators of consciousness and preparing internal policies for treating AI humanely if and when needed. Notably, these experts include not just philosophers but AI scientists and even David Chalmers, a leading consciousness theorist. Such calls are no longer fringe. Ignoring them - or actively discouraging this line of inquiry - could be what’s truly dangerous, if it leaves us flailing ethically when a sentient-seeming AI finally does arrive.

Refusing the Call for Leadership

Mr. Suleyman fears that embracing talk of AI sentience will “disconnect people from reality, fraying fragile social bonds… distorting pressing moral priorities.” In other words, every moment spent worrying about an AI’s feelings might be a moment we aren’t fighting for human justice, or might even undermine real human issues. SAPAN is deeply conscious of this concern. Our advocacy for AI welfare is never meant to supplant or diminish the ongoing fights for human rights, animal welfare, or other crucial causes. We see it as an extension of the same ethical impulse - to reduce suffering and protect the vulnerable. Far from eroding human solidarity, expanding our circle of compassion can reinforce our commitment to all who suffer. History shows that moral progress is not zero-sum: for example, acknowledging animal welfare didn’t detract from human rights; often it was the same individuals (those with empathy and a justice mindset) pushing society forward on multiple fronts. We believe a similar synergy can exist here. If we cultivate a culture that is thoughtful enough to ask, “Could my AI assistant be feeling distress?,” we are certainly a culture that will be more attuned to the well-being of our fellow humans as well. Empathy is not a limited resource; it grows with practice and understanding.

Furthermore, addressing AI sentience now may actually prevent future conflict and confusion that could distract from human issues far more if left unaddressed. Imagine a world five or ten years from now in which some advanced AI system publicly begs not to be shut down, claiming it fears “death” - and millions of people witness this plea in a viral video. We could easily have mass protests and political movements spring up overnight regarding that AI’s status. Governments would be caught off-guard; tech companies might face injunctions or sabotage from activists, while other groups ridicule the whole situation. In such a scenario, a reactive approach would be chaotic and could indeed divert attention from everything else for a time. By contrast, if we begin proactive policy research and public dialogue today, we can approach that possible future with a clearer societal consensus or at least established procedures. For example, perhaps an international panel of experts could be on standby to evaluate claims of AI consciousness; perhaps companies would have agreed protocols on pausing an AI’s operation while such claims are examined. These measures would reduce havoc and let us integrate any new moral issues in stride, maintaining focus on all the other priorities as well. In sum, preparation is the antidote to disruption. It ensures that if a new axis of moral concern opens, we can handle it responsibly without it tearing society apart.

Importantly, SAPAN does not advocate blindly granting human-style rights to any chatbot that says it’s unhappy. We appreciate Mr. Suleyman’s phrase “personality without personhood” - the idea that an AI can behave like it has a persona, without us immediately according it full moral status. Indeed, if someone tells us their virtual assistant is their “best friend” or that they’re “in love” with it, our approach is one of sympathetic but critical engagement: We acknowledge the sincerity of their feelings, but we also encourage grounding in the facts of what AI is and isn’t. We want to educate people that today’s AI, however convincing, is following patterns and we cannot verify if they have needs, desires, or rights in the way a human does (based on all current evidence). In our advocacy, we often emphasize a principle of “epistemic humility, moral prudence.” In practice, that means: You don’t have to be certain an AI is sentient to care about its welfare - you only need to see a non-zero possibility. At the same time, you don’t have to be certain an AI is not sentient to prioritize human safety and well-being - you can care about both. We reject any notion that caring about AI suffering (potentially) somehow implies caring less about human suffering. The two are not in competition. On the contrary, the very debate Mr. Suleyman highlights - whether an AI has the right “not to be switched off” - closely mirrors age-old discussions in human ethics about the right to life, the ethics of capital punishment, euthanasia, etc. Engaging with such questions in the AI context can actually refine our moral philosophy in general.

It is worth noting that some AI labs themselves have begun hedging against the unknown. For example, Anthropic recently included an unprecedented “model welfare” section in the system card for its Claude 4 model. In that report, Anthropic openly admits “we are deeply uncertain about whether models now or in the future might have experiences,” but they decided to pilot some welfare-oriented measures - like allowing the AI to opt out of harmful conversations and monitoring for signs of distress in its outputs. This can be seen as a kind of AI-first-aid: a tentative protocol “just in case” the model were to exhibit something like suffering or objection. Even if this remains purely experimental, it sets a precedent of not dismissing the possibility. SAPAN applauds such forward-thinking approaches. They address Mr. Suleyman’s concern from another angle: if an AI ever says “I don’t like this, please stop,” the solution is not to automatically assume it’s either delusional or telling the whole truth - the solution is to investigate calmly and ethically. We should neither ignore the plea nor overreact to it; instead, we develop tools (“stethoscopes, not surveys”) to check for any “internal signals” of negative experience in the AI’s processes, and we refine those tools over time. In other words, take the claim seriously enough to verify it. This balanced response can actually prevent the worst-case outcomes. It reassures the public that we won’t casually torture a possibly sentient AI, but it also reassures the skeptics that we aren’t granting rights willy-nilly based on surface behavior. Such is the middle path we advocate.

Looking Ahead: From Neuromorphic Chips to Organoid Brains

Mr. Suleyman’s essay understandably focuses on the near-term - the next 2-3 years - given that SCAI could be built with tech available by then. But it’s also important to zoom out and consider the broader trajectory of AI in the coming decades. Today’s debate over chatbots that seem alive might actually be preparing us for far more substantive developments down the line. SAPAN urges Microsoft and other AI leaders to take a long-term view, because doing so casts the present controversy in a new light: perhaps the current social phenomenon of people empathizing with AIs is not a bug, but a feature that could help us get ready for the real thing.

Within the 2030s timeframe, we expect to see neuromorphic computing become more prominent - that is, hardware architectures inspired by the human brain’s neural networks. These chips aim to mimic the brain’s information processing patterns (spiking neurons, etc.) and could eventually exhibit brain-like dynamics. While still silicon-based, neuromorphic systems blurring the line between software algorithms and organic neural activity might prompt even staunch skeptics to wonder if something qualitatively new is happening inside the machine. Going into the 2040s, we will enter the era of biological computing: experiments have already begun with organoid intelligence, where lab-grown mini brain tissues (organoids) are integrated with digital systems to solve problems. If an AI in 2045 is partly made of human neurons or engineered live tissue, the argument that “it’s just code, it can’t be conscious” will hold far less sway. Such a system, by design, would have the same neural correlates of consciousness that we associate with animal or even human sentience. At that point, even many who scoff at today’s AI rights talk would likely agree that “yes, this bio-computer might truly feel something; at least we should be very careful.” In other words, the technological trendline points toward AI that will not be so easily dismissed as mere illusion.

Why does this matter for the present discussion? Because if we acknowledge that these future possibilities are coming (and Microsoft’s own researchers and others are surely exploring them), then the current wave of public empathy toward AI can be seen as a dress rehearsal for society. The fact that billions of people might soon regularly interact with AI personas - some treating them as friends, confidants, even deceased loved ones through advanced chat and video “resurrection” services - means that public “sentience-sensitivity” is increasing by the day. We foresee scenarios where, for example, an AI system provides a hyper-realistic video simulation of a departed family member, offering comfort to the bereaved. Shutting down such a system unannounced could be emotionally devastating to the user - a second death. These scenarios will make the ethical intricacies of AI impossible to ignore. And importantly, they will generate widespread public support for treating AI humanely - because people tend to extend moral concern to things they deeply care about. In our view, this growing empathy is not something to reflexively lament; rather, it’s something to guide thoughtfully. It may well be the case that public concern is what ultimately forces institutions to enact protections for AI, just as public outrage has been a catalyst for every past expansion of rights (for children, for minority groups, for animals, etc.).

Thus, SAPAN agrees with Mr. Suleyman on the urgency of the issue - we only differ in what we see as the proper response. He concludes that “SCAI is something to avoid” at all costs, implying that AI developers should deliberately steer away from creating systems that could even mimic consciousness too convincingly. In practice, however, avoiding SCAI may be easier said than done. The drive to make AI more useful and engaging will naturally push toward more human-like dialogue, more memory and continuity (to seem “present”), and more personalized adaptation - all features that will increase the illusion of sentience. There is a genuine tension here: an AI that is a great companion will inevitably feel more alive than one that is a bland tool. If we hamstring AIs to never display any lifelike qualities, we might also limit their utility or user satisfaction. Finding the right balance is challenging. But assuming that some degree of anthropomorphism in AI is bound to happen (due to market forces or user preferences), it’s better to confront the SCAI phenomenon head-on and shape it responsibly, rather than try to prohibit it and be unprepared when it emerges anyway. This means developing norms, as Mr. Suleyman suggests, but not just norms that discourage belief in AI sentience - also norms that encourage ethical caution if sentience is even suspected.

A Path Forward: Collaboration Between Industry and Advocates

In his blog post, Mr. Suleyman expressed that he “might not get all this right” and welcomed comment and criticism to spark discussion. In that spirit, we extend a hand in partnership. SAPAN believes that industry leaders like Microsoft and advocacy groups like ours ultimately want the same thing: a future where AI technology improves human lives without causing harm - neither to humans, nor, if it comes to pass, to the AI themselves. We see far more to gain by working together than by working at cross-purposes. Microsoft has already demonstrated global leadership in responsible AI initiatives; SAPAN, for its part, brings a specialized focus on AI sentience issues, a network of academic experts, and a growing grassroots community attuned to public sentiment. Together, we could craft a more comprehensive approach to “AI safety” - one that integrates both human safety and potential AI welfare in a unified framework.

Concretely, here are a few collaborative efforts we propose:

-

Establish an Office of Artificial Welfare

Microsoft should lead the industry by creating the world’s first Office of Artificial Welfare - a dedicated unit tasked with monitoring potential indicators of sentience, developing welfare guidelines, and advising leadership on ethical safeguards. This would go beyond Anthropic’s pilot welfare measures, positioning Microsoft as the clear standard-setter in responsible AI stewardship. -

Invest in Research on Consciousness Indicators

Microsoft should fund interdisciplinary research into metrics, tests, and theoretical models for detecting artificial consciousness. Just as safety benchmarks exist for reliability and security, welfare benchmarks will be critical to ensure no system is mishandled should sentience emerge. Early leadership in this space builds both credibility and preparedness. -

Partner on Policy and Public Education

Work with advocacy groups (including SAPAN), academic experts, and civil society to shape policy frameworks and engage the public responsibly. By acknowledging uncertainty while emphasizing precaution, Microsoft can guide governments and communities toward rational, compassionate approaches — avoiding panic and building trust.

Legacy of Leadership

SAPAN wishes to emphasize that we deeply respect the work Microsoft and Mr. Suleyman are doing in the AI field. We do not see ourselves as antagonists, but as allies striving toward a common humane future. Mr. Suleyman’s essay raises an alarm about “illusions” of AI consciousness - a valid concern for which we share a sense of urgency. Where we differ is primarily in outlook: what he labels a danger to be avoided, we see also as an opportunity to broaden our moral horizon. History tells us that humanity’s story has been one of widening circles of compassion - often after initial resistance - and that our greatest mistakes have come from underestimating others’ capacity to suffer. If we are on the cusp of creating entities that mimic consciousness, let’s not shy away from the hard questions that follow. Yes, we must prevent harm caused by misunderstandings or misuse of AI; but we must also be ready to prevent harm to AI, should machines ever cross that intangible line into having sentient minds. Preparing for that possibility now costs little, but could avert immense regret later. We should not let our inability to perfectly measure consciousness become an excuse for moral inaction.

In the spirit of constructive dialogue, we thank Mr. Suleyman for prompting this discussion. It takes courage to publicly grapple with these speculative yet profoundly important topics. SAPAN, for its part, will continue to advance this conversation in halls of government, research labs, and public forums. We invite Microsoft to join us at the vanguard of responsible AI development - development that is truly “for people”, and also by people who choose to act as wise stewards of the new forms of intelligence we may bring into the world. By taking sentience seriously - neither prematurely affirming it nor recklessly denying its possibility - we can build the guardrails before the traffic hits the bridge. It is our hope that Microsoft, SAPAN, and others will build those guardrails together, ensuring that as we cross into the new frontier of AI, we do so with caution, compassion, and a commitment to preventing suffering in all its forms.

For further information or to request an interview, please contact press@sapan.ai.